The Dementia Inequalities Game

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia can be challenging, and is affected by many factors, including education, culture, stigma, GP knowledge, age, and dementia subtype (Burkinshaw et al., 2023; Mukadam et al., 2011). Where people do receive a diagnosis, the journey afterwards is often also characterised by various hurdles. These can include inequalities due to dementia subtype, living location, geographical differences in service provisions (‘postcode lottery’), availability of an unpaid carer, financial background, education, knowledge of available services, and many more (Giebel et al., 2021a,b, 2023a,b). Whilst these inequalities are evidence within the literature and in recent reports from Alzheimer’s Disease International and the Alzheimer’s Society, little is being done to overcome those barriers or educate the general public, professionals, and those living with or caring for someone with dementia about those.

Trying to do something different to disseminate evidence on dementia inequalities from my research group and existing evidence globally, we set out to co-produce a game on dementia inequalities. We wanted to co-develop a game on dementia inequalities which allows learning and socializing at the same time. Funded by the Wellcome Trust, we hosted four virtual and in-person workshops in total with 40 people living with dementia, unpaid carers, health and social care professionals, and Third Sector representatives. In the first two workshops, attendees were asked to first discuss inequalities and their own experiences surrounding diagnosis and care. Afterwards, they were provided with a blank virtual canvas asking them for ideas on how such a game should be designed.

Based on these workshops and discussions, our team went away to produce a very basic sketch of the potential boardgame, and asked attendees at workshop 3 to prioritise the highlighted inequalities, and match them to the game. Attendees were also asked to advance the design of the board. Following on from these discussions, we worked together with a game design company and fully developed the game, with the prototype tested by attendees at workshop 4.

Having designed this game with lived, professional, and voluntary experts was crucial to not only include key aspects of this topic area, but also create a game that is user friendly and of interest. The game is now available for sale via the Lewy Body Society webpage, although postage is limited to the UK. The game is suitable for anyone, and will be of particular value to health and social care professionals and those training to become care professionals, as it offers the opportunity to learn about dementia and associated inequalities in a social format over a game.

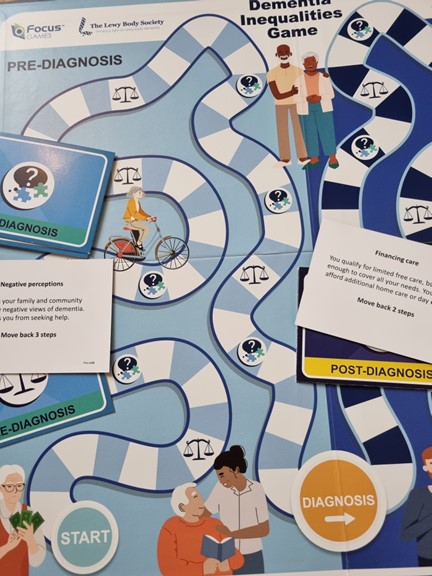

How does the game look like? Figure 1 shows a snapshot of the actual board, and both the inequalities and question and activity cards. The game can be played by 2 to 6 players, either as individuals or in teams, and players roll the dice for this snake-and-ladders-esque game to move around the board. The first half of the board depicts the pre-diagnostic stage, and the second half the post-diagnostic journey. When players come on an inequality card field (depicted by a scale), they pick up a card which either gives them a barrier (i.e. “Your GP doesn’t recognize you may have dementia as you are aged 55. You are not being referred for a specialist assessment. Move 3 steps back.”) or a facilitator (i.e. “You have a carer who knows how to navigate the care system. Move 2 steps ahead.”). Players can also come across general question and activity fields, where an opponent reads out the question or activity to them. The game lasts around 45-60 minutes, depending on how many players.

First findings from a general public game play workshop at the National Museum of Liverpool has shown that in over 50 members of the public aged 18+, playing the game has significantly increased knowledge about dementia and inequalities. The paper is published in Health Expectations, and you can read more about the game there too! We are currently evaluating the game in undergraduate students in psychology, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, orthoptics, nursing, and radiography, and are seeking funding to evaluate its impact on health and social care professionals. But there are many more opportunities, and within our INTERDEM Taskforce on Inequalities in Dementia, we are actively looking for funding and opportunities to adapt the game to different European countries.

Dr Clarissa Giebel, PhD

Department of Primary Care & Mental Health, University of Liverpool & NIHR Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast